His father was a corn merchant, and showing a keen interest in mathematics young Charles was soon apprenticed into a shipping firm. By the age of 22 he and his older brother Alfred started out on their own, founding the Booth Steamship Company in Liverpool. A fascination with how statistics could be used in society, as well as his Unitarian upbringing, helped convince Booth to undertake some sort of study of social conditions. The 1880s were a time of severe trade depression and were accompanied by shocking reports in the press of the depths of poverty throughout London. Most historians now reject the idea that Booth was spurred to action by the Social Democratic Federation Chairman H M Hyndman, who claimed that 25% of Londoners were living in poverty, but for whatever reason he had assembled a team of researchers to begin a initial survey of Tower Hamlets in 1887 that would then spread across London, lasting 15 years and being published in 17 volumes as Life and Labour of the People in London' in 1902.

His father was a corn merchant, and showing a keen interest in mathematics young Charles was soon apprenticed into a shipping firm. By the age of 22 he and his older brother Alfred started out on their own, founding the Booth Steamship Company in Liverpool. A fascination with how statistics could be used in society, as well as his Unitarian upbringing, helped convince Booth to undertake some sort of study of social conditions. The 1880s were a time of severe trade depression and were accompanied by shocking reports in the press of the depths of poverty throughout London. Most historians now reject the idea that Booth was spurred to action by the Social Democratic Federation Chairman H M Hyndman, who claimed that 25% of Londoners were living in poverty, but for whatever reason he had assembled a team of researchers to begin a initial survey of Tower Hamlets in 1887 that would then spread across London, lasting 15 years and being published in 17 volumes as Life and Labour of the People in London' in 1902.On to the sources.

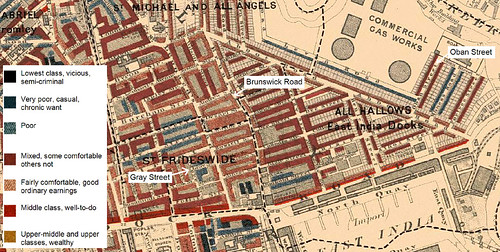

Booth and his team of researchers, which compromised a veritable stellar array of people later destined for important careers in social research and politics such as Beatrice Potter (not the Peter Rabbit lady), Gerald Duckworth, David Schloss and Clara Collett, walked every street in London and graded it on a number of criteria to assign it a level of poverty. These were colour coded onto a map showing the spread of poverty across the capital, and its these maps which make up the most striking part of Booth's work.

As you can see, not only were these sources incredibly detailed, but showed at a glance the geographical distribution of poverty, especially its relationship to the wider physical environment. Note for example the line of poor houses top centre running along the edge of the gas works, or the pocket of dark-blue and black in the bottom centre near the Docks.

The LSE, which holds these documents, has made huge efforts to put them online and the results can be found here:http://booth.lse.ac.uk/

What we'll concentrate on are the 'Police Walks', which were the notes of one of Booth's researchers accompanying a local policeman around a few streets to assess the poverty of the area. Specifically we'll look at a walk George Duckworth made with PC Cockett around parts of Deptford on July 27th 1899 (its B367 for you reference fans). Here's the link to follow as we go - http://booth.lse.ac.uk/notebooks/b367/jpg/69.html

One of the fantastic things about the Booth notebooks are the sense we get of late 19th century London street life. If we move on a page to 70-71 using the arrows at the top of the screen we find that 'Deptford Park in the centre is a broad open flat green space. Full of children this afternoon, hardly anyone there above 12 years of age except the police men and care taker'. Usually the streets visited by Booth and his investigators swarmed with children at certain times of the day, but here they've taken advantage of a green space to spend their time.

If we move over the page I hope you get the sense of moving through the streets of Deptford. Remember these notebooks are a record of a circular walk (see map on p. 69) and as such offer us a unique eye-level experience of late Victorian London. It is also, importantly, a sensory one; Trundleys Road has on the west side 'a bone boiler and animal charcoal maker; smell awful'. The smells of industry would have permeated 19th century city-life much more than they do now, and the smells of noxious industries would have determined a lower-class area, as those who could afford to moved out of range.

Turn over the page again (to pages 74-75) and we can see Booth's colour coding at work. Windmill Lane is 'less good' than preceding streets, which are of a comfortable working-class standard signified by pink on the map. Windmill Lane has slipped down to a mixture of light blue and purple, signifying a poorer class of residents.

If we move on to pages 76-77, which is the following days walk, we can see an example of the criteria that Booth's researchers looked for. In Staples Rents we can see the pencilled comment 'children dirty'. This was taken by Booth's observers as one of the marks of a respectable and financially stable working-class family, and is repeated throughout the notebooks. It is also a reminder however, that although a brilliant resource, we are looking at the world through a middle-class set of eyes. Although many working-class families would have agreed that a clean appearance was a indication of a child from a good family, many children were expected to fetch and carry for their parents, not to mention the dirt they would have picked up playing in the streets, and with bathing a time-consuming activity for working-class families we must take the vague label of 'children dirty' with some caution.

Thankfully Booth himself was aware of these problems, and conducted extensive interviews with local clergymen, police, charity workers, and some working-class people. These haven't been digitized but are available in the LSE archive.

Links:

Rosemary O'Day and David Englander - Mr Charles Booth's Inquiry: Life and Labour of the People in London reconsidered, 1993 and Retrieved Riches: Social Investigation in Britain 1840-1914 1995. These are the definitive works on Booth's survey of London, with the former relating in brilliant detail how it came into existence and was conducted, whilst the latter constitutes examples of how it may be used in a wide-range of historical fields. Plus Rosemary is one of my supervisors and both a great historian and a lovely lady.

The ever-good Spartacus offers an overview of the background of Booth and his contributors as well as their context. http://www.spartacus.schoolnet.co.uk/PHbooth.htm

And here's the link to LSE online again if people have missed it http://booth.lse.ac.uk/ which has an extensive further reading list.

Thanks for reading - this has been the first post (obviously) so any feedback on style or content would be appreciated. Also suggestions for the next post would be welcome!

The map is fascinating. Especially looking at streets I'm vaguely familiar with today, and how comfort and poverty could be the tiniest distance away from each other. I have a friend in Sao Paulo who says much the same thing about his own city nowadays. I loved Galsworthy's 'Forsyte Saga' but this map rather illustrates how their entire lives and stories were lived inside tiny pockets of wealth, which you can easily forget whilst reading it (you can see their houses here http://www.theforsytesaga.co.uk/images/map.gif which are all in a yellow orbit around the park on Booth's).

ReplyDeleteJames

(PS Don't take my display name as an endorsement of despotic monarchy I think I made it a long time ago and couldn't think of anything else to put. And had just been studying the 1630s)

I find the map fascinating! I'm an American, so I can't very well walk the streets in England, let alone hear detail about them from the 19th century.

ReplyDeleteThank you for posting all the links! (The style within this post is perfect. I say charge on!)

:-)

Good to meet you.

- Corra

The Victorian Heroine